Cyberpunk and the Sci-Fi Curve

Cyberpunk is a fan favorite literary, film, and gaming niche within science fiction, which has long since turned into a “supergenre;” sci-fi plays host to many popular subgenres (among them steampunk, alternate history, and post-apocalyptic survival). What sets cyberpunk apart from the rest, in addition to its recent rise in popularity, is the fact that it seems poised to fall in line with the sci-fi curve—in ways which its progenitors probably weren’t expecting.

This attribution is something which is normally associated with classic, mainstream science fiction, often of the “harder” (more realistically detailed) variety. It is frequently associated with names like Arthur C. Clarke, Gene Roddenberry, and Isaac Asimov, and even with such venerable writers as Jules Verne and H. G. Wells. Thousands of terrified radio listeners would certainly attest to the all-too-horrifying detail of Wells’ War of the Worlds.

The Science Fiction Curve: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Smartphone

The sci-fi curve is a famous idea, and is often referenced by authors. This happens in the same way that normal people—people who aren’t inspired to write fiction by the sight of an odd-looking shrubbery—tend to quote old sayings and popular expressions.

The curve references the seemingly prescient abilities of classic science fiction creators, whereby they appear to predict near-future feats of human invention. It can reference an idea or a trend, but is almost exclusively used to refer to technological achievement.

Here’s one famous example: back when futurists were talking about computers being “as small as a single room” by the year 2000, Gene Roddenberry was already envisioning the modern laptop computer and the smartphone (along with numerous other innovations). Yes, he placed them several centuries into the future, but that was in the face of some of the leading minds of the day not daring to go there at all.

Many people doubted that some of those ideas which we now take for granted would ever be possible, even within the time frame that Star Trek was invoking.

As a side note, some of the most far-fetched of Star Trek’s ideas may be forever impossible (or not), but they do present us with profound existential questions: watch CGP Grey’s most bodacious video, The Trouble with Transporters, just in case that accident from The Motion Picture has stopped giving you nightmares after almost forty years. Also, click here for nightmares, because I’m a helper.

The Deal with Cyberpunk

If you’re familiar with cyberpunk already, go ahead and skip to the next section if you’d like. If you choose to continue, please understand that this is only meant to be a light, topical overview of the subgenre, not a thorough and comprehensive examination.

The seminal, classic work of cyberpunk with which the greatest number of people are most familiar—dedicated fans of the subgenre aside—is most likely the 1982 film Blade Runner. There are other works of film and literature (as well as a variety of games, songs, and other popular media) which are more outstanding in terms of the genre’s attributes, and there are other, equivalently famous works which include the odd cyberpunk-themed element, but Blade Runner brings it all together.

The story of Blade Runner is easy to follow, although its underlying themes are profound. A former cop, played by Harrison Ford, is extorted by his old superior into taking up his specialty one last time. He’s to track down and “retire” four replicants who stole a shuttle, killed the people on board, and came to Earth illegally. Replicants are genetically engineered bio-mechanical androids, so like unto humans that specialized training and psychological examinations are required to ferret them out. Over the course of the film, Ford (as Rick Deckard) comes to question the rightfulness of his mission, and the viewer is exposed—not only to the violence of the replicants—but to the monstrous actions of those who created them.

The film exhibits several major aspects of cyberpunk. Here are some of the highlights:

- The Alienated Loner: The hero is a solitary, brooding and asocial figure, who is extorted by an autocratic authority into doing a distasteful job with which he’s long become disenchanted. He lives alone, and is unaccustomed to friendship.

- The Megacorp: More powerful than governments, the world of the cyberpunk subgenre is dominated by global-spanning corporations. They operate their own police forces, wage urban war against their competition, oppress the people who work for them, and follow only their own rules—with impunity.

- “High Tech Low Life:” Genetic engineering has reached a point where animals—and people—can be designed and grown to exacting specifications. Technology is extremely advanced, but we’re also shown a society that is fractured and crumbling. Crime and poverty are rampant. The world is filthy—almost as messy and disgusting as the people who live in it.

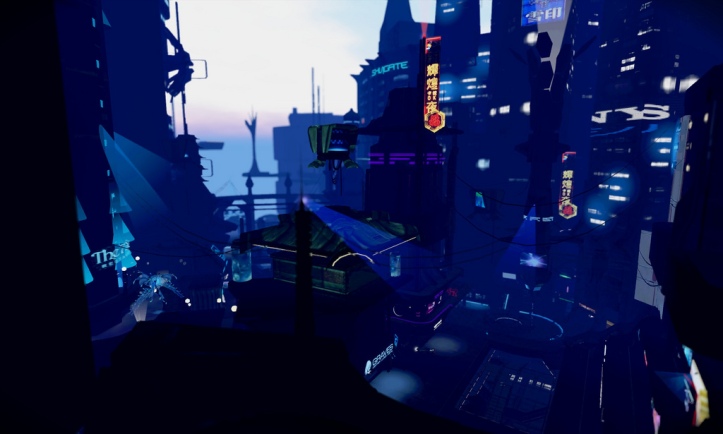

- Terra Firma: The cyberpunk setting is almost always an overcrowded, resource-stretched, near-future Earth—the better to confront issues like social disenfranchisement. Cities consist of enormous, towering buildings, with increasingly unsuccessful and unfortunate people living lower down in the superstructure.

- Film Noir: Cyberpunk is dark, brooding, suspenseful, and atmospheric. It makes heavy use of narration (which is still present in some versions of Blade Runner) and often follows a structure similar to that of a classic detective story.

How Cyberpunk is Setting the Curve

Science fiction has always mirrored social and political issues relevant to its time. Small wonder, then, that cyberpunk is becoming more relevant: our technological advancement is outpacing our growth as a society. Cyberpunk reflects a setting of advancing technology, which is often used in strange and unintended ways: people aren’t sure what to do with all of the capabilities at hand. It mirrors social unrest, complaints about oppression, and a strong feeling of disenfranchisement: you’re on your own, and nobody is out there pushing for your better interests. Major characters are often connected to a computer network twenty-four-seven—sometimes literally; even the most functional are barely getting by.

That, in itself, isn’t enough to make it dominate the sci-fi curve, but consider the following:

The Latest in AI: Autonomic Function

We have been making huge leaps in artificial intelligence, and many of these strides are going unnoticed and unappreciated: we forget that there is much more to intelligence than problem-solving and holding a conversation. Everything that we take for granted about how our brains work is part of our “intelligence,” from controlling our heart rate to regulating our body temperature.

Fifteen years ago, we had the technology to perform complex brain surgery and study a person’s genes, but creating a robot that could walk upright was still virtually impossible. The power, complexity, and autonomic function required for something like walking is taken for granted by many people.

Today, we’re on the verge of creating robots that can perform brain surgery. Part of the development of AI technology has been research into things like perception, and autonomous functions: a truly intelligent robot should be able to delegate walking and other basic functions to its background processes, just as we do. Scientists have built two- and four-legged robots which can recover their balance after being struck by a stout kick, or with a sledgehammer. The way they maneuver is smooth and organic, to the point where it triggers a creepy “machines aren’t supposed to do that” vibe in many who witness it for the first time.

Cybernetics: Personal Enhancement

We’re developing prosthetics with autonomous functions that react to our muscle movements—or are directly connected to our brains. A man with two artificial legs can walk, run, sprint, and jog up and down stairs.

One of the major components of cyberpunk has always been cybernetic enhancement. People deliberately have limbs, organs, and other parts of their body augmented artificially—or replaced, with alternatives of superior design, whether biological or mechanical. This is very much mirrored by current endeavors—and not only with prosthetics. Consider the ongoing effort to help transplant victims avoid rejection by literally growing replacement organs from their own cells.

At present, this is done for medical reasons. There is a neurological disorder which causes those who suffer from it to crave the amputation of specific limbs, but in general, people don’t get body modification of this magnitude for purely voluntary reasons—certainly not legitimately. That seems likely to change, however, when prosthetic limbs inevitably pass beyond the point of being relatively delicate and fragile, and begin to surpass our biological counterparts in function.

Recommended Reading

- The essential cyberpunk reading list—Gizmodo; includes Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep, the basis for the film Blade Runner.

- Cyberpunk novels—Goodreads

- Cyberpunk 2077—CD Projekt Red, developers of GOG.com and the Witcher game series, are working on a cyberpunk-themed game of truly phenomenal proportions.

Reblogged this on sjwolford and commented:

Really interesting!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks! I’m embarrassed to say that I actually completely left out the one thing that prompted me to write this in the first place. If you’re looking to learn more, look up information on CRISPR. It could allow us to cure all disease within the next 50 years or so… or, it could be used to create designer people.

LikeLike